|

4/5/2022 0 Comments April 05th, 2022The autumn I turned sixteen, I bought a car from my boss at the Country Club where I worked. I remember the feeling of excitement when we met in the parking lot and exchanged the money. In my hands were now the keys to a Ford Explorer Sport, a car I needed not only to get to school, but also to cushion my social standing in a crowd where SUVs were the coolest thing since Abercrombie cargo pants.

It’s hard to believe that a gangly kid like me was legally able to drive a hunk of explosive metal around my hometown in those years. My sense of the repercussions of an accident were dim at best, and, like most kids, I drove my car with all the gusto and irresponsibility of a teenager high on his newfound freedom. Though nothing bad ever happened while I was driving, I have since heard horror stories about the car accidents that have taken the lives of teenagers and adults alike. Nowadays, the thought of reckless sixteen-year-olds taking to the road in fast cars makes me shudder a little, wondering how we ever thought it was okay to let everyone drive around in these machines. Car ownership had its golden age, even if it was never safe to begin with. By the year 1930, more than half the families in the United States were car owners, a number that would continue to steadily grow throughout the decades. At that point, the road was nothing less than an adventure, offering the oft-wished for freedom hanging at the edge of each person’s dreams. It’s not a reach to suggest that cars, in their most mythological form, represent freedom. In post-World War II America, the booming economy and growing middle class made the personal car what it is today, pushing suburbs farther out and offering every American the chance at their own little slice of the good life. In this way, cars represent much more than practicality. They represent romance, abandon, opportunity. All you have to do is cruise the strip in a convertible with the perfect song on the radio — perhaps Don Henley’s Boys of Summer or Bryan Adams’ Summer of ‘69 — to grab a slice of this effervescent joy. Public policy attempted to make this dream a reality for the average American. 1956 saw the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act, connecting cities through quick-moving freeways that drastically cut down travel times. Cities built parking lots everywhere, hoping to attract the car-driving masses with their new disposable income. The importance of the car in American society was sealed, and its dominance as a transportation option has hardly been questioned since. Even in my silly green Prius, I know how the romance of traveling by car. Cruising on the Pacific Coast Highway with the salty wind in my hair, I can experience, even on the hardest days, a little bit of that bliss the open road offers me. Anything and everything is possible when I know that these four wheels can take me anywhere my heart desires. Here in the United States, we love opportunity and individualism, and in our culture the car has come to represent both. Once granted, taking away someone’s “freedoms” is seen as an affront to the whole idea of America, a place where we’re supposed to be able to do whatever we want, whenever we want. In that era, sprawl and infrastructure hadn’t gotten close to the levels we see them nowadays. You could drive most places without encountering mind-numbing traffic jams (although Los Angeles still had its fair share of 50s traffic). Yet parking was becoming an increasingly testy issue in cities, as residents looked for places to put to place their cars in congested areas. As cities faced this issue, most gave into the demands for more parking and wider highways and gutted their towns, allowing endless car-dependent suburbs to pop up on the periphery and imposing parking minimus on new businesses opening up. Car use in America has reached such a turning point. For many people, the traffic and congestion they encounter on a daily basis is absolutely mind-boggling. During certain times of the day, they will have no choice but to crawl along interstates and city streets just trying to get home from work. Many emerging technologies go through this process, first being touted as the solution to humanity’s problems and quickly becoming a part of the problem. In the course of a century, car use has gone from a new, exciting way to get around, to a huge issue for safety, public health, and land use. When it does, the negative effects of the new technology can become a real problem for day to life, hindering people more than it is helping them live better lives. Each year, 1.35 Million People die worldwide in road-related deaths. The danger cars pose to society, including those using alternate forms of transportation such as cycling and public transportation, is real. Turns out that people, overall, aren’t that good at driving. Since 1899, 3.6 million people have died in traffic accidents in the United States alone. We hardly think about it anymore, but we’re all driving around death machines as we hurry around congested cities trying to text someone on our smart phone in the process. And, of course, we’d take another form of transportation, but work is too far away to take transit, bike, or walk to. Some claim that transportation planning is stuck in an old-fashioned mentality of “paving our way out of our cities’ congestion” (Tumlin, 2012). The problem is, “paving our way out of congestion” doesn’t fix the problem, and can even exacerbate it. According to this way of thinking, the solution to traffic is just to add another lane of it. That’ll fix the problem, right? It’s just another one of those false reasonings and myths that drive a lot of the planning around transportation systems in our country. One of those myths is that drivers are actually paying for the roads they use, which, turns out, just isn’t true. The current gas tax only pays for about half the spending on roads, meaning that those roads you are “paying for” by driving your massive car are actually heavily subsidized by, you guessed it, all of us. This wouldn’t be such a huge problem if car infrastructure didn’t act as a huge barrier for other forms of transportation. Wide roads make it difficult for pedestrians to get around, and disconnected roadways and networks make transit networks and biking a nightmare. The American obsession with driving and the personal vehicle has not only destroyed the option of any other transportation form in many cities, it has led to environmental destruction, segregation, cultural disconnection, and head-pounding traffic jams that likely make each person want to scream in horror at the situation they’ve got themselves into. ... Transit is available in most cities in the United States, but in most cases it isn’t a practical option. Outside of New York City, Boston, or Chicago, the answer is most likely an emphatic no. Taking transit is most cities is going to lead to long waits in adverse weather conditions, multiple transfers, and a transportation time nowhere near as time-effective as driving your car. The real transit-destroying problem is the land use types that cars have allowed to happen. It just isn’t practical to serve spread-out strip malls and backroad businesses miles away from the city center with efficient transit. The type of auto-oriented development in this country might as well be referred to as “auto-only development.” If you have a car, great. If you can’t afford one, then screw you. Take this from someone that had a nightmare experience just trying to get to the DMV in my mid-sized city last year. Every DMV in the city was located miles away in some distant, sprawling part of the city — Not one office was located in the relatively accessible city center. Not only was it far away, but scary to get there by bike or foot as angry drivers fly by you with a not-so-gentle throttle of the gas pedal. The car culture is not only deeply embedded in this country, but it also encourages toxic behavior. In some place, cyclists are harassed by cars and screamed at to “get off the road.” In rare circumstances, they’re even killed by car drivers on power trips. That’s not even mentining the tens of thousands dead on our roads every year. There are people that need to drive for various reasons, like freight delivery companies and small businesses that carry supplies and provide vital services. But the vast majority of our traffic in cities is extraneous, and actually can hurt our economy. The lost time “vital drivers” like freight trucks, delivery vehicles, and service providers experience from sitting in traffic is costly to the economy, and to everyone it provides for. But is there a different way? Can we forge a new transportation path forward that doesn’t include the personal car as the only viable transportation choice for most Americans? A Different Future For Transportation So what does a “different future” look like? It means rewinding the clock on “auto-dependent” land use and envisioning a way in which we can create micro-cities within cities, where everything you need is within walking distance of your house or apartment. Schools, jobs, food, and essential services would all be available without having to drive long distances to get there, allowing people to form communities that aren’t separate by massive parking lots and seven-lane streets. When cars are relegated to an auxiliary form of transportation in this country, we might be surprised at the costs we no longer have to pay, and the extra money we have to spend on infrastructure that isn’t for the automobile. Americans, after all, have been shown to “pay a hefty bill for driving.” And it’s not only paying for new roads and road maintenance, it’s the “unpriced costs” of crashes, healthcare, air pollution, and sprawl that are equally shouldered by all of us. “For more sustainable cities, the challenge for designers is to provide most of the needs of daily life within walking distance while maintaining the social and economic benefits of being tied to the larger region." (Tumlin, 2012) As Tumlin puts it in “Sustainable Transportation Planning,” the most important factor in our city transportation offerings is choice. As Americans, choice should be at the top of our priorities. Choice obviously doesn’t mean requiring everyone to take one form of transport (such as cars), but allowing residents the ability to choose what works best for them and their circumstances, while also providing an equitable framework in which to get around and take advantage of the economic and social opportunities of the city. The social part of this transportation equation can not be downplayed. Though cars allow us to get around fast and efficiently if there’s no traffic, the land use they encourage fractures communities and leads to city where no one cares to know each other. When you don’t walk or bike to local neighborhood spots, it’s harder to run into neighbors or form bonds along the way. The reason things ended up this way are much too long to list. A combination of public policy, market failure, propaganda, and bad pricing and tax models have propped up the car at a monumental cost to society. This has created a system where the end user, in this case a car driver, pays nowhere near the actual cost of driving and parking that vehicle. The end result of this? The compulsory motorist. This person doesn’t drive because they want to, but because they have to. There is no choice for them, because they live in a place where work, essential services, and activities are too far away or inconvenient to get to by any other form of transport. What do cars need, after all? Parking. Cars are parked for 90% of their lifespan, which means that’s mostly what they’re doing — taking up space. Because of this, parking in the United States takes up a space nearly the size of Delaware and Rhode Island Combined. And who pays for parking? All of us. The cost of parking, and the burden it places on small businesses and developers, is another thing that hurts our economy and stifles growth, leading to cities with miles and miles of lifeless swaths of concrete that serve no other purpose than to place hunks of metal on them. Looking around, you can see how parking lots divide and space out buildings, creating a situation where uses in the city are hopelessly far away from each other, making driving to them the only viable choice. It also represents a loss of value that land could offer to people, offering them more places to go within walking distance in their neighborhood. ... Was the personal car a mistake? When I’m behind the wheel and the traffic is light, I can see why it’s nice to drive. Especially when that perfect songs comes on, and all the lights are green. Sometimes it’s just so easy. But I also see a different way. A way in which I get exercise instead of sitting in a car; a path in which I interact with the world along the way, seeing interesting things on the street and meeting business owners and members of the community. It’s that informal type of relationship with the world that walking and taking public transit offers us — that’s what driving takes away from us, leading to isolation and ill-health. After all, who hasn’t gone to Europe and come back obsessed with the walkable cities, beautiful architecture, and accessible train systems. That’s the sort of connectivity that is possible in the U.S. if we rethink our cities, and our relationship with the car. At it’s best, driving opens up the world, offering us places to go and things to do. But at its worst its a trap, destroying our cities and leading us into a zero-sum-game where nobody wins. In this age of technological leaps and increasing isolation, we must be careful to not let driving be another way in which we cut ourselves off from the world outside. Is it time we take back our cities from the car, re-humanizing and revitalizing them? Yes, I think it is time.

0 Comments

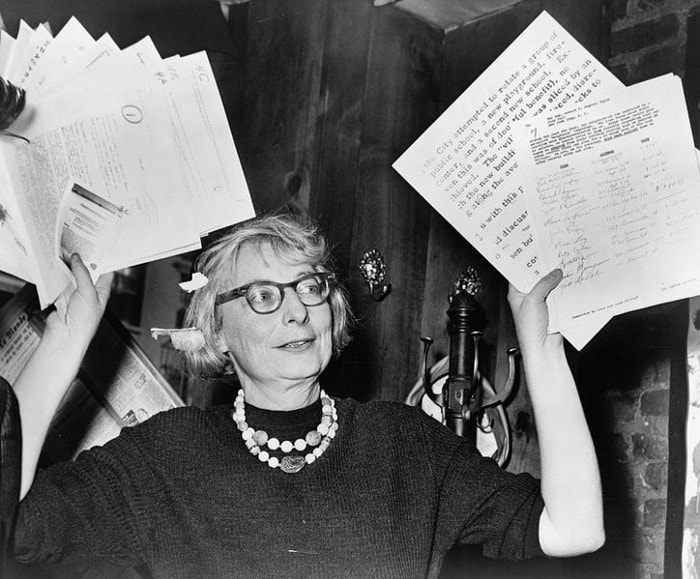

The year is 1968. 51-year-old author and activist Jane Jacobs takes the stage at a local hearing about the new highway proposed to go through the southern part of Manhattan. The project is called Lomex, or Lower Manhattan Expressway, and has stirred controversy ever since it was suggested by the famed public works director Robert Moses.

The event was a formality scheduled by the New York State Department of Transportation so that they could say they collected public opinions. They expected it to be a by-the-book meeting, but it turned out to be nothing of the sort. Soon the crowd was chanting “We want Jane!” over and over, summoning the famous urbanist to the mic. She denounced the project, encouraging those in protest to join her on stage, where the stenographer’s notes were soon strewn about as the State DOT tried in vain to control the situation. Jacobs would soon be arrested and taken to the police station, even as protestors continued to shout “We want Jane!” outside the jail. This meeting, and Jane’s subsequent arrest, would turn the tide of opinion surrounding Lomex, a superhighway project that would have cut across Manhattan and destroyed a large chunk of what is now known as Soho (which as then a poor and struggling commercial area). The area was saved because of the efforts of many dedicated New Yorkers, including the well-known author Jane Jacobs. In the book Wrestling with Moses, the author Anthony Flint recounts the clash between Jane Jacobs and her nemesis, Robert Moses, bringing us front and center into the struggles for urban space and neighborhoods that would define a generation of New Yorkers, and change Urban Planning for years to come. The battle over Lomex wasn’t the first time Moses and Jacobs found themselves on the opposite sides of a fight. There were several battles between the two in Mid-20th-Century New York, all of which Flint describes in gritty detail. Jacobs had won an early victory in the battle to save Washington Square Park in the late 50s, and then a few years later rescued her own neighborhood — Greenwich Village — from an Urban Renewal project. The fight over the Lower Manhattan Expressway, also known as Lomex, is the third battle detailed in the book. Lomex was, in many ways, the pet project of the famed public works director Robert Moses, who was arguably the most powerful man during that era of New York City. With the force of Moses behind it, it was very unlikely that any project would be shot down in years prior. With money promised by the Federal government (thanks to the 1956 Federal Highway Act), Moses thought that it was now or never to build a high-speed expressway that connected New Jersey and Brooklyn across Manhattan Island. On the other side ideologically was the historic preservation movement, which sought to preserve notable buildings and build neighborhood pride in New York City. With the destruction of beautiful buildings like Penn Station still controversial with locals, it was becoming increasingly easy to garner support in favor of a saving, rather than destroying, older structures with architectural value. This idea of preservation instead of destruction would take hold in mid-century NYC, uniting people against the perspective of powerful men like Moses, many of whom wanted to modernize New York City by clearing out older buildings — all in the name of automobile traffic and urban renewal. Historically, the building of interstates would prove to be a monumental and controversial move for the United States at the time. What was once a mess of roads and highways across the continent would now allow for the quick and efficient movement of cars between major cities. Yet these roads had to go somewhere, and where they usually went was through poor, multicultural neighborhoods that lacked the political clout and financing to fight these decisions. In the 1950s on, a number of cities across the country destroyed historic, often minority neighborhoods to build interstates through downtowns and out to suburban areas. Many of these neighborhoods will never be the same, scarred by the demolition of people’s legacy, tradition, and sense of home. For more on this, check out the Vox video at the end of this article. By the time that Lomex was officially proposed in the early 60s, Jane Jacobs had grown tired of constantly fighting the system to save urban neighborhoods and stop renewal projects. She was against the highway, that was for sure, but didn’t know if she had the energy for another battle against an ill-conceived public works project. Robert Moses, power broker and public works extraordinaireNevertheless, Jacobs was brought into the fight against the interstate, which would have destroyed hundreds of structures in the area now known as Soho. One of these buildings was a Catholic Church, which served the local area that had yet to become the hip fashion hub of these modern times. This priest, named Gerard La Mountain, would be the one to convince Jacobs to help them stop Lomex. The visions of New York drawn up by the designers of Lomex were nothing short of dystopian in style. Coming out of the tunnel, triangular structures would have stretched over the submerged road, possibly serving as apartments and restaurants for New Yorkers. The two crossings on the east side of Manhattan would have featured strange towers lining the bridge entrances. You can see the mockups in the image below. So how did they win the fight? Jacobs and company employed many different techniques to help sway public opinion and make people pay attention. One was to flip the narrative of the project. The Lomex protesters referred to the project as the “Los Angelization” of New York, which was quite the insult at the time. They also appealed to their local representatives, people with the clout and influence to sway local organizations and government action. When local politicians stand up against a project, such as in the case of Lomex, people are much more likely to pay attention. The protesters also benefited from Jacobs’ fame at the time. With such a famous (and controversial) writer and urbanist on their side, they could be sure that the story would, in the least, garner a lot of attention. Jacobs was also great at organizing people in a common cause and inspiring them to act. By the 1970s, Lomex was declared officially dead by local leaders, and with the many buildings in the area with official historic designation, is unlikely to ever be revived again. All these years later, Jacobs influence still rings loudly in American Urban Planning. Not only is New York City preserved for future generations, but Soho is now a prime example of a hip urban neighborhood, attracting the rich and the famous to its cast-iron buildings and wide streets. For better or worse, historic preservation now coexists with gentrification, as the poor are pushed out by money and real estate speculation. |

AuthorWriter. ArchivesCategories |

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed